The Hidden Passage

A documentary-style podcast that explores the supernatural by recalling the beliefs of the past to inform the present. Delving into mythology, the occult, high strangeness, and alternative history, the show draws from philosophic, spiritual, and scientific perspectives to contemplate our greatest mysteries.

The Hidden Passage

Midwinter: Saturnalia, Yule, & The Origins of Christmas

The period of time from late December to early January was spiritually significant to ancient cultures. The ancient midwinter festivals directly shaped our Christmas and New Year's holidays. This episode traces the history from the very beginning all the way to modern day, exploring feasts like Saturnalia and Yule. Discover the true meaning of the season, the major religious themes and historical events that brought us to where we are today.

All episodes are available in video format on YouTube

Send your personal experiences (spiritual, paranormal), questions, comments, or business inquiries to: hiddenpassagepodcast@gmail.com

You can also send a voice message through SpeakPipe

Follow on Instagram & Twitter

Please consider rating/ leaving a review. Thank you for your support!

In December, come the shortest days of the year. The sun reaches its lowest point in its precession across the heavens, known as the winter solstice. This marked the mid point of winter. Having endured months of bleak conditions being confined indoors, our northern ancestors, just as we do today, felt the need to find ways to assuage the feelings of boredom and despondency which the season could induce. Without the modern comforts we enjoy today, winter took a much greater emotional toll, and could even threaten the lives of those who were not fully prepared to face it. It is this need for solace in the dark night of the soul, as well as a key astronomical event on December 21st, the winter solstice, which gave rise to ancient mid winter religious festivals and their spiritual successor, Christmas, becoming the most widely cherished and celebrated holiday in the world.

The winter solstice, held both tragic and hopeful spiritual significance to the ancients. It took place three months after the equinox when, in an act of cosmic treachery, the solar god had been mortally wounded. For in this imperfect world, the greatest good is often met with resistance. In the Freemasonic tradition the three killers of enlightenment, fear, ignorance, greed correspond to the three winter months and their houses, responsible for the death of the savior, who is martyred in his effort to bring light to the world. On an individual level, this process was representative of the human struggle for spiritual ascension against the lower parts of their nature which kept the soul in bondage. The winter solstice symbolized the gates of heaven, at which the higher nature repeatedly succumbs to the lower, preventing entry, highlighting the apparent futility of the great work within the material world.

During this astronomical event, the sun is at its lowest point in the sky and appears to stop moving for three days. The word solstice in Latin means “the sun stands still”. As when something dies the body ceases to move, this was a sign that the solar god had perished. After this period of three days, the sun appears to resume motion, changing direction in a northward precession. This was a sign that the god had been reborn. When conditions seemed to be at their worst, the greatest miracle took place. This was the promise of salvation which the deity embodied in his own regenerative power, conferring onto humanity and the world. Despite this repeated thwarting, the spirit of good persists.

Midwinter festivals were structured around the two major aspects of this solar event, beginning on the solstice and ending when the sun began to resume motion, the archaic predecessors to Christmas and New Year’s, two holidays which were originally one in the same. While this was an important point in the god's renewal, sometimes the full resurrection was considered to take place over the next three months, being completed by the spring equinox.

The process of the sun’s resurrection illuminated a great metaphysical truth, that darkness was the ultimate source of creation. As the light is born out of the darkness, just as a child is conceived within the darkness of the womb. In it is contained all possibilities, a primordial chaos from which all forms are ordered. “Light is a manifestation of life, and is therefore posterior to life. That which is anterior to light is darkness, in which light exists temporarily but darkness permanently. As life precedes light, its only symbol is darkness, and darkness is considered as the veil which must eternally conceal the true nature of abstract and undifferentiated being.”

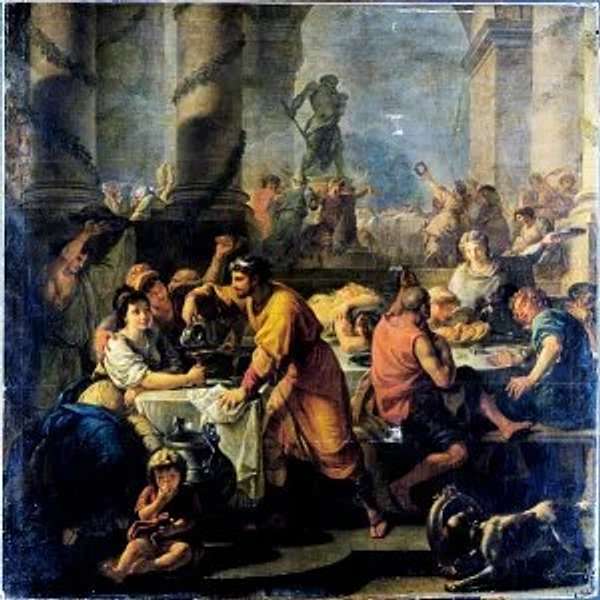

When we think of the spirit of Christmas, themes of joy, festivity, charity, and human connection might come to mind. One of the most ancient mid winter festival traditions which perhaps had the most influence in shaping Christmas was that of the Romans. Theirs was celebrated on December 17th and over the following 2-7 days, known as Saturnalia. This was a preparatory observance for the new year feast of Kalendae on January 1st, when the power of the sun was though to be returning. It was for this reason that Kalendae held supreme religious importance. Yet despite this, Saturnalia was by far the most popular, no doubt due to its rites of revelry. It was referred to by the poet Catullus as the best of days. And yet, strangely, it was not the sun god Sol who was honored on Saturnalia. When the power of the sun had been extinguished, a peculiar, ancient memory resurfaced, the memory, of a golden age, a time when another king ruled the heavens, and human beings lived in paradise on earth. His name was Saturn, a sovereign god, a god of plenty, of beginnings, and ends, the primordial, universal monarch born from the union of the Earth Goddess Gaia and sky god Ouranus. Under Saturn’s reign there was bounty upon the earth, an abundance of food and resources, and no need for humans to compete with or subjugate one another for material gain. They lived in a state of innocence and harmony, virtuous by nature. An association was made between Saturn and the Greek god Kronos, and in the writings of the poet Hesiod we are given further detail with regard to the golden age. “[Men] lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief: miserable age rested not on them; but with legs and arms never failing they made merry with feasting beyond the reach of all devils. When they died, it was as though they were overcome with sleep, and they had all good things; for the fruitful earth unforced bare them fruit abundantly and without stint. They dwelt in ease and peace.”

In this era, it is said that human beings were bestowed with godlike qualities, and the gods lived among them. They did not age or fall ill, and lived long lives, only dying when they decided to pass on, at which point they would become daimons, spirit beings which could be seen visibly. It is also said that animals had the ability to speak like humans, a belief which is likely responsible for the legend that on Christmas Eve, animals have the ability to speak. However beneficent and wise, Kronos had dethroned his father Ouranus to come to power, and became paranoid of a prophecy which stated that he would in turn be overthrown by one of his offspring, and so he became cruel, consuming his children in an effort to avoid this fate. Nonetheless, he was usurped by his son Zeus, causing a cataclysmic end to the golden age. Him and his consorts were cast into Tartarus, the abyss, and restrained, thus in later depictions he was bound at the feet, only being unshackled during Saturnalia. Under the reign of Zeus, human beings were made to be inferior, and when they did not follow the gods, were destroyed and remade, initiating a progressive devolution of the human race. With each new age and formation of man, he fell to a lower state as a form of punishment, from the golden age, to silver age, to bronze age, and so forth.

The myth of the golden Age and the subsequent fall of man can be seen not only in Greco-Roman but also in Hindu and Judeo-Christian traditions and is famously echoed in J.R.R Tolkien’s conception of Middle Earth and the fall of Numenor, inspired by the Greek Atlantean myth of the destruction of an advanced pre-Diluvian society.

During Saturnalia, class distinctions were temporarily dissolved, slaves were waited on by their masters and were allowed to speak and act freely, and mock kings would be elected to preside over the celebrations, a guise of Saturn himself, symbolizing his temporary rule while the solar king was away. This role reversal was a nostalgic reenactment of the idyllic Saturnian era when all people were equal and free. Shops, schools, and government buildings were closed, and certain moral restrictions such as gambling were loosened. During the religious ceremonies on the 17th, a sacred fire would be kindled by the vestal virgins and kept lit until the new year. These were a group of priestesses who took vows of celibacy and religious devotion. The symbolism of the sacred fire may have been that through each new cycle, before each beginning, and after each end, the imperishable, eternal flame of the creator remains at the heart of creation.

In the days following, people celebrated by feasting and drinking, playing music, gambling, and socializing. The idea was to make merry an invoke this golden era when everyone was happy, possibly in an effort to bring about its return. Holly and ivy were used as symbolic decoration. Remaining green year round, they were symbols the eternal nature of spirit which renewed the world. Gifts were exchanged, especially candles, as similar symbols of this undying light. As the paragons of perfection, the ancients often sought to do as the gods did in order to become like them, and so this may have been symbolic of the divine gifts of Saturn during the golden age. Kalendae featured similar rites, with a stronger emphasis on gift giving in order to bring luck for the coming year.

As to why Saturn was worshiped at this time, there are a few possible explanations. The Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry suggested it was because the sun passed through the astrological house of Capricorn during the winter solstice, which was known to be ruled by Saturn. As a god of generation, he may have been seen as responsible for the resurrection of the sun. As a god of time, he would sensibly stand as the gatekeeper between the old year and the new. Also being a god of agriculture, he would’ve also been seen to have the power to bless the crops of the upcoming season, which were to be sown in January. Later, we will come back to this question and look at a more exotic and controversial theory, that identifies Saturn as the original, or true sun.

While most of our Christmas traditions seem to trace back to the Romans, we will nonetheless now turn our attention towards the evidence for an ancient mid winter festival in the British Isles and Nordic states. The nature of this festival, and therefore how it might connect to Christmas, is less understood due to lack of documentation. Despite this, there is enough information to suggest that this was indeed an important religious observance in the same manner as the other solar holidays we have discussed. The oldest testament to this is found in the alignments of certain ancient mound sites. From 3200 BC to 3000 BC, the architecture in the British isles shifted from the building of megalithic shrines to circular burial enclosures which also served ceremonial purposes. One of the most impressive of these is Newgrange in Ireland, the entrance of which is aligned so that the rays of the rising midwinter sun shine directly into the main chamber. On the isle of Orkney north of Scotland, the burial mound of Maes Howe aligns in a similar manner with he rays of the setting midwinter sun. In Southern England are the cursuses, earthen structures resembling long narrow trenches, which likely had some ritual function. The largest of these in Dorset, stretching over six miles long, points directly towards the midwinter sunset. These structures do suggest an ancient religious observance of the midwinter sun, however it should be noted that of the hundreds that exist, only a small number of them are known to have such alignments, and many do not have any identifiable alignments at all. This makes it difficult to establish the existence of a widespread solar cult, or any continuation of solar worship into the Iron Age or later periods. Evidence in myth is also lacking, such as in the Irish Ulster cycle, showing mostly evidence for the seasonal festivals.

Despite this lack of widespread continuity, there is still enough evidence to suggest that midwinter festivals were firmly entrenched in European cultures long before the creation of, and were the spiritual predecessors for the Christmas holiday. St Patrick himself wrote in the 5th century about the Irish pagans who worshiped the sun. Bede stated that for the Anglo-Saxon English, the most important annual festival took place on December 24th, which was called Modranicht, or “Mother Night”, which marked the new year, wherein people would keep watch throughout the night. The historian Snorri Sturluson claimed that the Nordic peoples celebrated the ancient pagan festival of Yule, which involved sacrifice for good crop, in contrast to the “winter nights” festival mentioned last episode which allegedly made sacrifice for an easy winter. This relates to the Romans propitiating their agricultural god at the same time. Yule was said to last for three days. One Icelandic account tells of a warrior who postponed single combat until afterwards, so as to not break the sanctity of the festival. More evidence comes to us in a series of denunciations made by churchmen, some of whom were the most renown fathers of the early medieval church, which spanned west into Germany. Archbishop Wulfstan of York, whose province had recently seen an influx of paganism from a Viking settlement, complained about “the nonsense which is performed on New Year’s Day in various kinds of sorcery.” Among these appeared to be divination magic to see what the new year would bring. Finally, in Wales, we have strong literary evidence of the existence of their midwinter festival called “The New Year Feast”. The last, and perhaps most important, piece of evidence, can be seen in an attempt by the English Crown to move the new year, and thus the newly adopted feast of nativity to march, in an effort to make sense of the Roman month names they had adopted and its original calendar which put March as the first month. This change remained in place for almost six hundred years from 1155 until 1752, and despite this, virtually everyone continued to practice their religious rites centered around the new year in December/January. If Christmas was a new holiday that was truly embraced over preexisting ones, the transition would’ve theoretically been easy. This alone is enough to suggest a longstanding pre-Christian tradition existed in the cultures whose legislators unsuccessfully attempted to uproot it. Despite these changes, all emotional attachment to these original dates remained firm. Furthermore, it is evident that the spiritual significance of these traditions was intimately tied to the unique solar event which occurs during this time. While we don’t know exactly how many of these ancient festivals were celebrated, we can probably assume they involved both religious ceremony and communal festivities not unlike the Romans.

While the midwinter festivals suggested hopefulness and optimism among those who observed them, we must also acknowledge the dark spiritual forces that people believed to be at work during midwinter. After all it was the death of the sun, and temporary plunging into darkness, which as we know is symbolically connected to evil. Like Samhain, there appears to be a supernatural element of danger believed to present at this time, as evidenced by the records of such defensive magic, even surviving into the Victorian era. The original purpose of hanging mistletoe seems to have been to ward against evil spirits, preventing them from entering the home. It was common in Ireland and Scotland to keep the mistletoe hanging until New year’s had ended to keep the fairies away. One account tells of a belief held among the superstitious, that for every twig left behind after the removal of the greenery, that one goblin would haunt the home.

In Germanic paganism, there is the concept of the Wild Hunt, which scholars have connected to the midwinter festival of Yule. This was a host of supernatural beings in pursuit of humans, a sort of reckoning, led by a god or goddess, in the case of its Germanic form, Wodan, or Odin, as he is known in Scandinavia. . They were believed to fly through the sky at night, often astride war horses. This hunting party was variously described as being comprised of draugrs, valkyries, elves, or ghostly dogs. Draugrs were essentially the proto-zombie, animated corpses of the dead, said to guard the treasures buried in their tombs. Valkyries, were female godlike beings who were said to rule the fates of those in battle, summoning fallen warriors to their designated hall of Asgard in the afterlife. Elves, were humanoid supernatural race of beings, said to live in the wilderness. The ancient elves of Germanic belief were distinctly different from later concepts of the fae folk which we explored in earlier episodes. They were described as similar to human in appearance and stature, but more fair, similar to Tolkien’s portrayal in his novels. This is also now suggested to be the case for ancient Irish and Anglo-Saxon concepts of similar beings as well. This is a good example of how ancient beliefs can change or become misconstrued from their original meaning over time. As people began to abandon the old religions to Christianity, their gods became dark and strange. The Wild Hunt is theorized to have gone through this metamorphism as well, emphasizing only the dark and cthonic qualities of what were in reality dynamic concepts. Folklorist Jacob Grimm in its earliest conception, the Wild Hunt visited “the land at some holy tide, bringing welfare and blessing, accepting gifts and offerings of the people, floating unseen through the air, perceptibly in cloudy shapes, in the roar and howl of the winds.” He believed that Christianization gave it a new visage as “a pack of horrid spectres, dashed with dark and devilish ingredients.” In some parts of Christian Britain, they were thought to drag the souls of the damned to hell.

Despite this, it appears that the Wild Hunt in one aspect served a grim reaper type function, collecting the souls of those who were fated to die, and serving as an omen of death and war to whoever witnessed it. The wild hunt was said to commence at the fall equinox and end at the spring equinox, reaching its peak during the winter solstice. The identification of the Wild Hunt as a winter phenomenon is obvious, as winter is associated with death, not only because of its affect on nature, but also because many more people die in winter than any other season. It is often associated with strong winter storms and winds. The wild Hunt would even make its way to Britain in 1127, being recounted in the Peterborough Chronicle as an actual event with several reliable witnesses. "Many men both saw and heard a great number of huntsmen hunting. The huntsmen were black, huge, and hideous, and rode on black horses and on black he-goats, and their hounds were jet black, with eyes like saucers, and horrible. This was seen in the very deer park of the town of Peterborough, and in all the woods that stretch from that same town to Stamford, and in the night the monks heard them sounding and winding their horns." [39]

Perhaps both the negative and positive aspects of the Wild Hunt are part of its nature, a dualistic nature, that could come in the form of punishment or reward, in a karmic dispensation of judgment, bringing resolution to all things, a clearing of the slate for the new year. It would make sense that there would be a belief in divine judgment coming at the end of each year, just as it came at the end of life. Perhaps this could help to explain a more familiar figure of the season, one who rides through the night sky, leaving gifts for good children, and coal for the misbehaved.

We will now turn our attention to Christmas, which in context of the midwinter festivals, begs the question, why was it decided that it would be observed at the same time? In fact there is no reference in the Bible to the date of Christ’s birth, and best estimates place it somewhere in October. Furthermore, “It now seems to be generally accepted that the Nativity stories are an extreme case in the Christian gospels of inventions by authors to place Christ in traditional Jewish salvation history.” Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the sun. With so little foundation for a historical birth, then, why was December 25 identified as the date? The reason was tactical, relating back to the process of syncretization mentioned in the Easter episode. The church saw the popularity of the midwinter festivals, which were even celebrated by Christians themselves. Instead of trying to eradicate such a beloved tradition, it was estimated to be much easier to allow people to retain their religious customs in form and simply adapt them to the worship of Christ.

“It was a custom of the pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that day,” Syrus.

The placement of Christmas on this day was done by Roman decree in 354. This replaced the cult of the Unconquered Sun in Rome, which had replaced Saturnalia in 274, both of which were done with political impetus to unite the increasingly factionalizing Roman empire. In 567 the council of Tours formalized the 12 days of Christmas from the 25th to January 6th, which was dedicated to the baptism of Christ, under the Greek name Epiphany. Several other holy days related to events in the life of Jesus and his disciples were invented to fill the period of days. This extension was an attempt to absorb the pagan feasts into one Christian festal cycle. Christmas would obviously retain preeminence among them, and the ancient practice of New Year’s gifting would be transfered onto it and given new meaning. the story of the wise-men and their veneration of the infant Jesus, bestowing gifts of frankincense and myrrh, would come to capture the imagination of medieval Europe. Gifting came to symbolize the acknowledgment of and devotion to Christ as the savior. Monarchs would take part in this custom as a gesture of allegiance to the Church.

Christmas would prove to be problematic for Christians, spurring confusion over its true nature, so much so that Pope Leo the Great himself felt compelled to remind people that the object of worship during Christmas was Christ, and not the sun. Indeed the similarities are all too evident as both deities were savior figures divinely conceived on this day, and both underwent a resurrection, again suggesting the construction of the Nativity story based on earlier mythical archetypes. Adding to this confusion was the allegorical use of light in association with Christ, as he himself declared “I am the light of the world. The one who follows me will never walk in darkness.”

This identity crisis would remain unresolved for hundreds of years, coming to a head during the protestant Reformation and the Church of England’s scrutiny any religious tradition without scriptural basis. Inevitably, the holiday would become a focal point of religious and political conflict, a struggle between theological reformists and the masses who insisted on retaining their folkways. Christmas was subjected to a series of unsuccessful campaigns of suppression and even outright abolition, before finally being left alone. However, for a significant period in the middle ages, it was largely embraced by political and religious authorities and everyone from royalty to peasantry, along with many pagan symbols and rites which were infused into the Christian holy day.

We will now turn our attention to the celebration of Christmas in medieval Europe. This was much more akin to the Saturnalian festivities than the holiday we recognize today. Instead of private, low key observances in the home centered around family, medieval Christmas was much more communal, centered around public gatherings and merrymaking. The streets would be filled with drunken revelers. People enjoyed singing carols, dancing, playing games, telling stories, and cross dressing. Like the mock kings of Saturnalia, a person would be appointed to guide the festivities, taking on a king of fool’s, jester-like persona. He was known as the lord of misrule. Rites of hospitality and charity were also common, with nobility hosting feasts on a grandiose scale. In 1377 King Richard the second hosted a feast for over ten thousand people. The meal of twenty eight oxen, three hundred sheep, and a slew of other dishes, required the services of two thousand cooks. 200 tubs of wine were also consumed. Hospitality was practiced at all levels of society, with even the poor being expected their doors to to the needy stranger.

Another popular custom was that of entertainments such as song, dance, and theater performed by the lower classes for the crown, in exchange for donations and gifts. This was known as mumming, derived from the Greek “momo”, meaning, mask. These entertainers would don colorful costumes and disguises, spangled with bells and sequin. Elaborate visages of heroic knights and creatures such as peacocks, and dragons, and devils were created for the mummer’s plays . Groups of people would also travel from home to home to entertain families.

The Christmas generosity of nobility was sometimes less romantic than it appeared. Kings would be criticized for extorting gifts from their subjects, and the gentry would complain about having to oblige the solicitations of the poor. At certain points in history, mumming eventually fell out of favor with the crown due to people using it as an opportunity to commit crimes. It seems these festive entertainments may have been done primarily out of necessity, as the poor were struggling financially due to lack of gainful employment in winter, as there was no farming to be done. Eventually the practices died out with the creation of the middle class.

Many pagan midwinter symbols found their way into early Christmas and carried right through to today. Just as the Romans, and most other ancient cultures, used greenery and light in their midwinter festivals, so too did medieval Europe. The motivation for the use of these is obvious, providing comfort and reassurance during the season that deprived people of plant life, light, and warmth. As magical tools, they would’ve been used in an invocation of the forces that brought these things back into the world, being symbols of such. Holly and ivy were used especially, and it is said that there was an old belief that ivy represented the female element, and holly the male, their combination representing the divine union which begets new life and correlates to spring. Whatever religious significance they had was lost by the middle ages, but they were nonetheless used in great amounts for ornamentation, being some of the only available greenery at the time. They could be seen filling the halls of all manner of buildings, from churches, castles, to the homes of commoners. “The middle aisle is a pretty shady walk, and the pews look like so many arbours on either side of it. The pulpit has such clusters of ivy, holly, and rosemary about it that the light fellow in our pew took occasion to say that the congregation heard the Word out of a bush, like Moses,” The Spectator, 1712.

The hanging of mistletoe in the doorway seems to be another foliage rite with ancient origins, and was also eventually adapted into a more innocuous and secular form, the kissing bush, now simply referred to as mistletoe, the main plant out of which the bush was constructed. It emerged as a popular tradition among common folk. It is interesting to note that the kissing bush seems to be an attempt to invoke the wild spirit pagan festivals like Saturnalia within a confined and controlled space which allowed Victorian society to cautiously explore a certain loosening of social restrictions. It was given a romantic mystique by writer Washington Irving, who identified it as the beloved and sacred plant of the Druids.

The second pagan symbol brought into Christmas ceremonies was light. This was popular all over Europe, with candles commonly being lit on Christmas eve, known as Candlemas. The same can be said for the Christmas log, which was meant to be large enough so that it could burn through the entire festal cycle, and its embers used to start a new fire for the new year. This log went by many names in many areas, but it most widely known today as the Yule Log. It’s specific origin is uncertain, but it would make sense for it to have originated in Scandinavia, where winters are coldest and require large, long burning fires to stay warm. These practices may have been a remnant of older sacred fire and candle rites such as that of the Romans during Saturnalia. While their purpose was certainly practical and ornamental during this time, we do see some arcane significance attached, as the belief was often expressed that they also provided spiritual protection for the home.

The fusion of Christianity and paganism would eventually start a protracted conflict, beginning in the mid 16th century. Tensions were brewing as church services were being disrupted by drunken revelry. The trials of Christmas began in 1561, when the Scottish Kirk Calvinist Church declared, correctly, that the Papists had invented Christmas and all related feasts, with no basis in scripture. They had sufficiently petitioned the government to an extent that it was able to dictate policy, and eventually overthrew it altogether, proceeding to abolish Christmas wholesale. All forms of celebration were prohibited. Even making snowballs was illegal. In 1573, the Kirk tried fourteen women for “playing, dancing and singing of filthy carols on Yule Day.” The leaders of the craft guilds were prosecuted for idleness. Those who continued to hold the feast were excommunicated. Inspectors would even come to peoples’ homes to search their kitchens for Christmas goose. This movement would spread to the Church of England, who until then had only taken a mildly critical stance. In exchange for military aid from Scotland, England agreed to give kirk reformists influence in Britain. Upon a new evaluation by the church, Christmas was deemed a mixture of Catholic superstition and godless hedonism, and restrictions of the same manner as Scotland were put into place. This would fuel an already growing animus towards the Protestant English parliament which had gained political power over the crown. On Christmas day in 1647, riots erupted in several counties. Tensions between the Parliamentarians and royalists escalated into a civil war, with the abolition of Christmas being used as a rallying call, helping to engender overwhelming public support of the crown. Whatever resentment had been growing for the crown among the people was put aside, now being looked upon favorably in comparison to Parliament, who also burdened the people with higher taxes and military quartering. But the rebellion was crushed, resulting in the execution of king Charles the first and exile of his heir, ending Christmas as a holy day until the Restoration. This however was not able to stop secular observances, and without Christmas mass, the festival would actually become even less Christian than before, ironically compounding the very issue the Kirk had sought to resolve. Members of Parliament would complain of being kept awake at night by rowdy party-goers on Christmas eve. In 1660, Charles the second marched his army into England and defeated the Parliamentarians and restored the crown, nullifying every legislation that had been passed since the coup had taken place. Christmas carried on much as it had before, now with the full support and participation of the monarchy.

The next major historical period in the evolution of Christmas began in the 19th century. The industrialization of the West was a major influence in the course of its development. Authors like William Wordsworth, Washington Irving, and most notably Charles Dickens, used the idea of Christmas as an allegory for the moral reform that was needed to re-mediate the social division which resulted from the emergence of business tycoons and an increasing stratification of economic classes. Just as the ancient Romans waxed nostalgia for the golden age, these writers turned to old traditions as an answer to the growing discontent, as models of virtue and harmony. Before this, employers, sanctioned by government, didn’t recognize Christmas, and expected people to work. The sentiment being expressed by media was that it was an archaic custom that had no place in the developed world. Despite this, there was a concern among the middle class of a growing disparity of wealth, and a negative impact on familial bonds, as working parents were increasingly distanced from each other and their children. These authors sought to crystallize and express what was already being felt by many people. The pinnacle of these efforts came in 1843 with the release of A Christmas Carol by Dickens. Ebeneezer Scrooge was an indictment of the selfishness that industrial society produced, and his arc outlined a redemptive path for the rich to transmute the very product of their avarice into a means of atonement, through charity. He attached piety to the feast, and portrayed Christmas as being centered around the family and children, a radical departure from the public festivals of old. Prince Albert was also instrumental in this shift, having an image published of his family at home home gathered around a Christmas tree.

There is a common myth that the modern Christmas was primarily invented and peddled onto the public by industrialists seeking to sell more products. The reality is that the commercialism of Christmas was a response to the growing desire of the public to celebrate the holiday and subsequent demand for more products. With more dispensable income, a newfound respect for the intimate parent-child bond, and a need to keep them occupied while they were away, the toy industry experienced a massive boon.

The last missing piece of the Christmas puzzle, the Rosetta stone, the personification of the Christmas spirit, is of course, Santa Claus. The idea of personifying Christmas was first conceived in the early 1600’s by writers who described him as an “Old reverend gentleman in furred gown and cap.” He was dubbed Father Christmas. At this point he was akin to the lord of misrule, a more foolish rather than serious character, the embodiment of seasonal merriment. It was not until the historical Saint Nicolas of the Netherlands that this idea would begin to take its recognizable shape. St Nick was known for his charitable nature. The most famous example of this is his payment of a dowry, which the soon to be wed daughters parents could not afford. He did this by leaving gold in their shoes. This is the origin of stockings. Saint Nicolas would be used as the inspiration for the final iteration of Santa developed by New York City professor and writer Clement Clark Moore in his poem, “ Twas the night before Christmas”. The description therein was not a mortal saint, but a magical being from the north pole. The description contained many of the key elements we associate with Santa today, a portly elfin man with a bushy white beard, who flew through the sky on his sleigh, climbing down the chimney to leave gifts for children. Clark’s only motive for writing the poem was to amuse his children. To his frustration, a copy was leaked to a newspaper, and quickly became a sensation. The modern Santa was born in new York City. Christmas, with its new mascot, was set to become the most popular holiday in the world.

At this point, we will come full circle, and bring the idea of Santa back to the ancient midwinter festivals. It is assumed by most scholars that the only possible ancient inspiration for Santa was Odin and the wild Hunt. Indeed, the description of the old bearded man, flying through the night sky, enlisting the service of elves, bears a direct similarity. My personal theory, however, is that Santa, Odin’s Wild Hunt, and Saturn, can all be linked with the common mytheme of judgment. As I have demonstrated earlier, all three of these figures display a dualistic nature, capable of bringing about both reward and punishment, embodying both dark and light aspects, just as the observation of the winter solstice acknowledged both the darkness and the return of the light. This punitive aspect is only somewhat evident in the popular western form of Santa, but in the old Alpine traditions, he is known to enlist the service of Krampus, a demon who comes to abuse and abduct misbehaved children. There are also similar figures, such as the the Icelandic witch, Gryla, who roams the streets during Christmas, also looking for unruly children to abduct. At one time, before the re-focalization of Christmas towards children, there was a feeling that everyone should take a moral inventory at the end of the year.

Saturn represented abundance but also limitation. In Hinduism, Saturn is the god of karma, capable of swinging both ways in the act of judgment. He knows if you’ve been bad or good. The color of Saturn is black. Judges wear black robes in court. Saturn is the last planet, the last hurtle in the ascension through the spheres in Hermeticism. As the sun passes through Saturn’s house on the winter solstice, he is the gatekeeper between the end of old cycle and the new. He is also the god of time, which encompasses the beginning and end, and everything in between. Time and judgment are related because time will tell. All things resolve in time, what is sewn is inevitably reaped. It is not coincidental, then, that Saturn is the agricultural god. The seed, like the darkness, represents potential, and Saturn is there to make sure that our intentions and our actions correlate to how that potential descends through the spheres and condenses into form, from everything into one thing, hence why Saturn is both abundance and limitation, why Saturn meant sacrifice, giving up all that could be for what is. He may dash our hopes and dreams, show us the err of our ways, but at the end, descends from his throne in the north to bestow the gift of life, another chance to start anew, year after year.

What can we learn from the history of this thing we call Christmas? Maybe that it is a testament to fundamental aspects of human nature, the need to celebrate life, to connect with one another, to honor the transcendent. There are certain basic forms of human expression that we are impelled to express, and we have always insisted on doing so, in spite of the whims and schemes of institutions who would seek to control or prevent it, or inject us with their own contrived ideas. The manner in which we observe may change, but the core spirit that drives us remains unmoved by tide of history. Nothing can stop us from celebrating.

I want to wish everyone listening a merry Christmas, good Yule, Io saturnalia, or whatever winter holiday you choose to celebrate, and a happy New Year.